A Brief History of

Historic Preservation in Houston

The earliest homes built by settlers of European descent in the Houston area were near the coast and accessed by boat. Whether wealthy or poor, the building forms were simple with only one or two rooms. The primary objective was survival and protection from the harsh climate.

Prior to Texas’ independence from Mexico, the conditions were primitive, but improving. The above house was most likely a log cabin that was eventually clad in clapboard siding. Note that the house eventually burned down. This is a reoccurring theme in the earliest structures in Houston.

Following independence, during which the Republic of Texas was a sovereign nation, Houston was founded and the present day street grid established. While the building forms remained vernacular, materials began to be imported and this allowed for more refined facades.

After annexation by the United States, the first multistory buildings began appearing. Shortly after the above photo was taken the entire block burned down.

Within a decade, the block was completely rebuilt with even taller buildings…

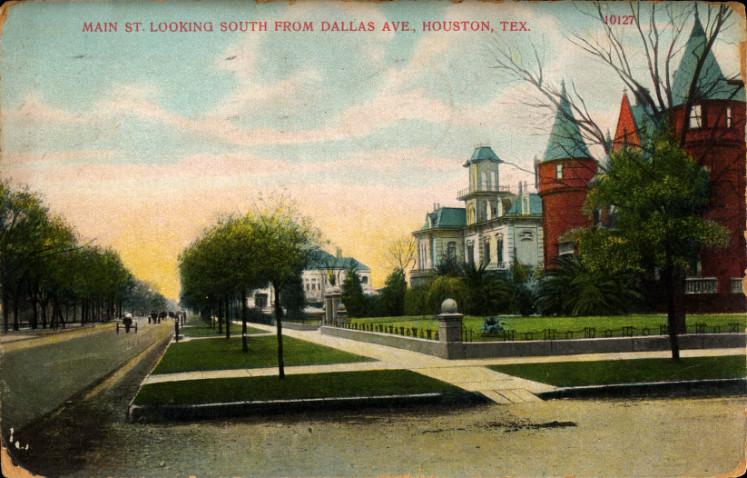

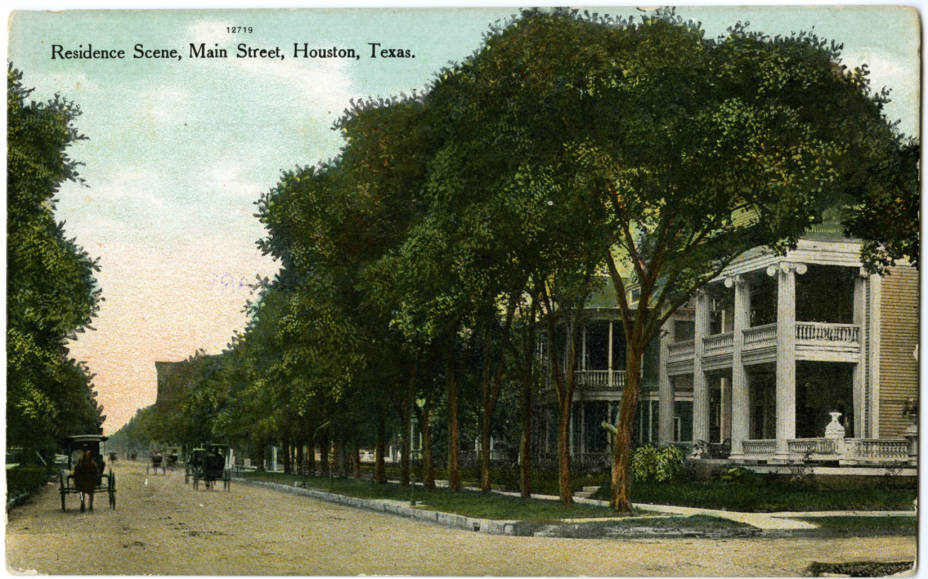

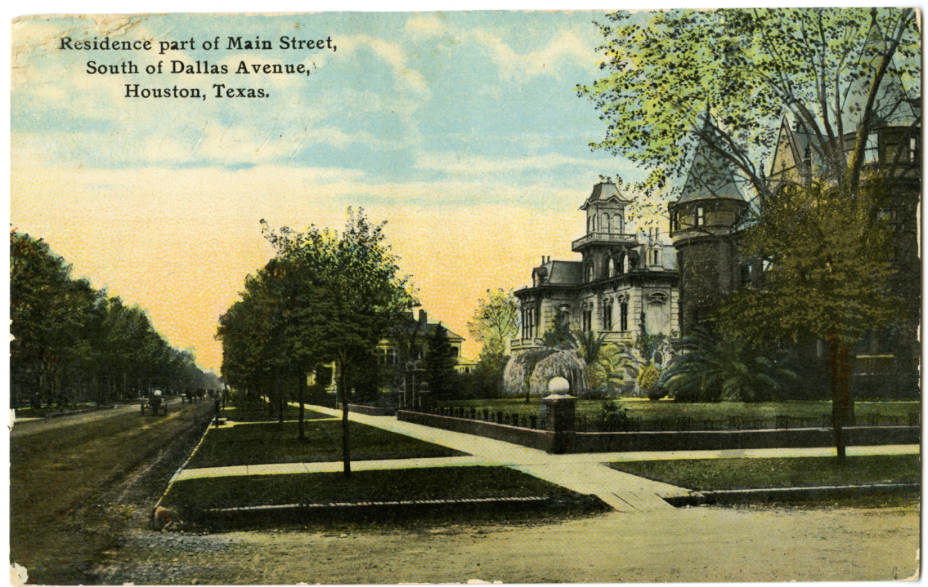

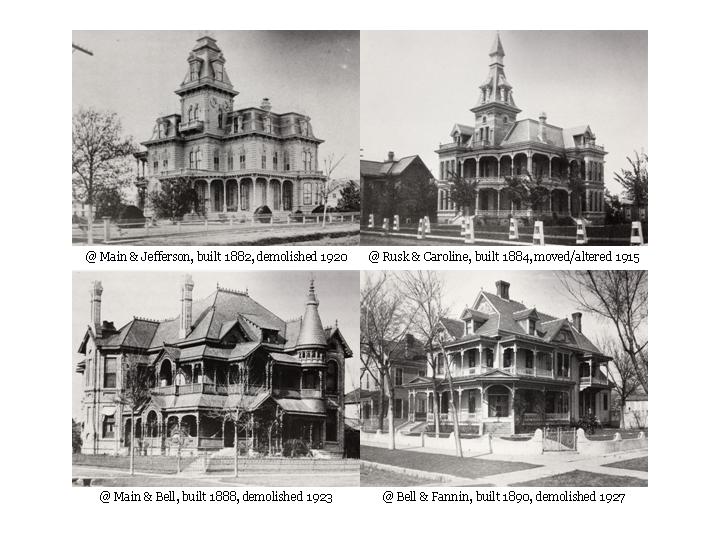

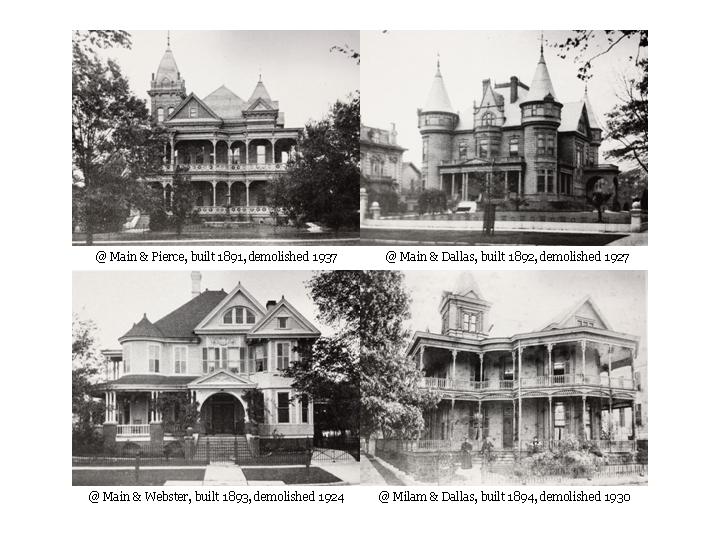

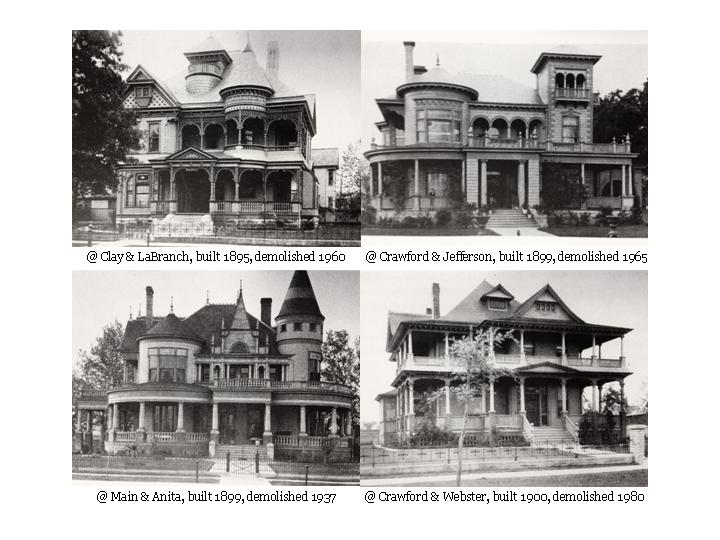

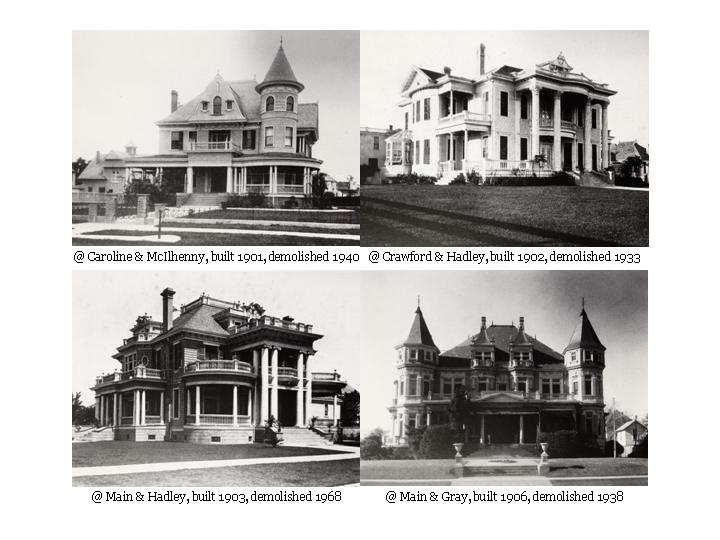

By the 1890s, coupled with the exploitation of the bayou system to export cotton, Houston had become the railroad center of Texas. Wealthy business owners didn’t want to live in the dirty, original sections of downtown and Houston’s first outward migration began when these businessmen built large estates about a half-mile south on Main Street in the “country.”

And by the turn of the century a major hurricane had destroyed Galveston, the largest city in the region, and oil was discovered near Beaumont. This led to the construction of the Houston Ship Channel and the rapid urbanization of Houston.

The above postcard shows the 1200 block of Main Street at Dallas looking south. The present day Houston Pavilions would be on the left, with the Courtyard Marriot on the right, and the now vacant Foley’s/Macy’s behind the cameraman.

These houses numbered one to four a block and always faced east to take advantage of the prevailing breezes off the Gulf of Mexico, cooling the main house and keeping the smell of manure from the carriage houses in the back away from the main house.

The grand old houses on Main Street, at 5,000 to 10,000 square feet each, were as large and elaborate as any other mansions across the country. In the time before personal income tax as we know it today, businessmen showed their wealth by importing the finest building materials and architectural styles of the time.

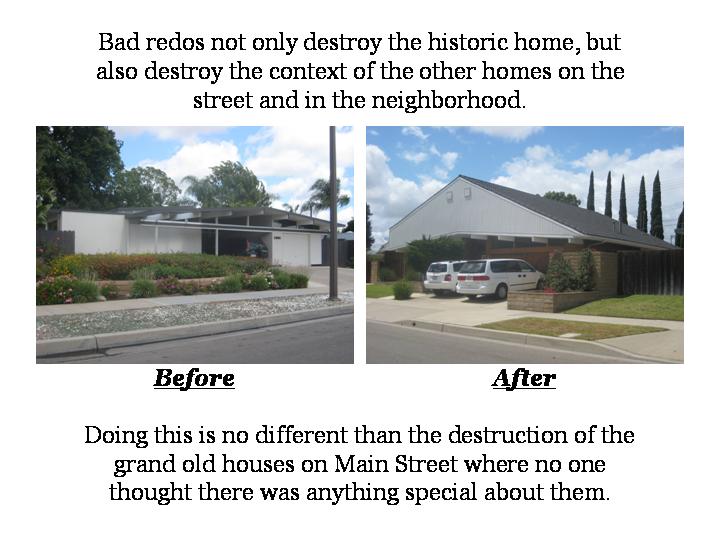

However, the lives of hundreds of grand old houses on and around Main Street were short lived. They were not destroyed by fires or hurricanes, but were all deliberately demolished in the name of progress to make room to build auto parts stores, Piggly Wiggly’s, and sometimes just a parking lot.

As cotton was drying up as the dominate industry, oil was literally flaring up…

By the 1920s, the first skyscrapers begin appearing. The above photo shows downtown looking north with the Rice Hotel in the center. The residential streets immediately adjacent to these taller buildings would have had a similar feeling to the neighborhoods around the French Quarter, while the grand old houses on Main Street that stood just a few blocks farther south would have had a similar feeling to the Garden District in New Orleans.

But, by the 1970s, all that remained of Houston’s original, walkable Victorian neighborhoods had been destroyed and replaced with surface parking lots for the even taller skyscrapers going up every few years. The above photo shows downtown looking southwest where the present-day Discovery Green park would eventually go.

Fortunately, in 1954 a group of citizens could see the city’s past quickly disappearing and they came together to form the Heritage Society to save the below house from demolition.

The Kellum-Noble House, in the shadows of skyscrapers downtown, is still in its original location. Despite the site being used for Houston’s first school, first park, and first zoo, the City wanted to demolish the structure anyway because it was in the way. Thankfully, the Heritage Society was allowed to preserve the building and expand Sam Houston Park to include 9 other historic structures from other parts of the city.

The Nichols-Rice-Cherry House has been altered and moved several times over the years. The roof has been restored to its original shape, but the wraparound porch has been lost to time. William Marsh Rice, the namesake of Rice University, once lived in the house before being murdered by his butler.

Pillot House, built in 1868 at McKinney and Chenevert (now the site of the George R. Brown Convention Center), moved to park in 1965.

This house and its occupants witnessed the destruction of Houston’s original residential neighborhoods. The family donated the house to the Heritage Society upon moving away from downtown.

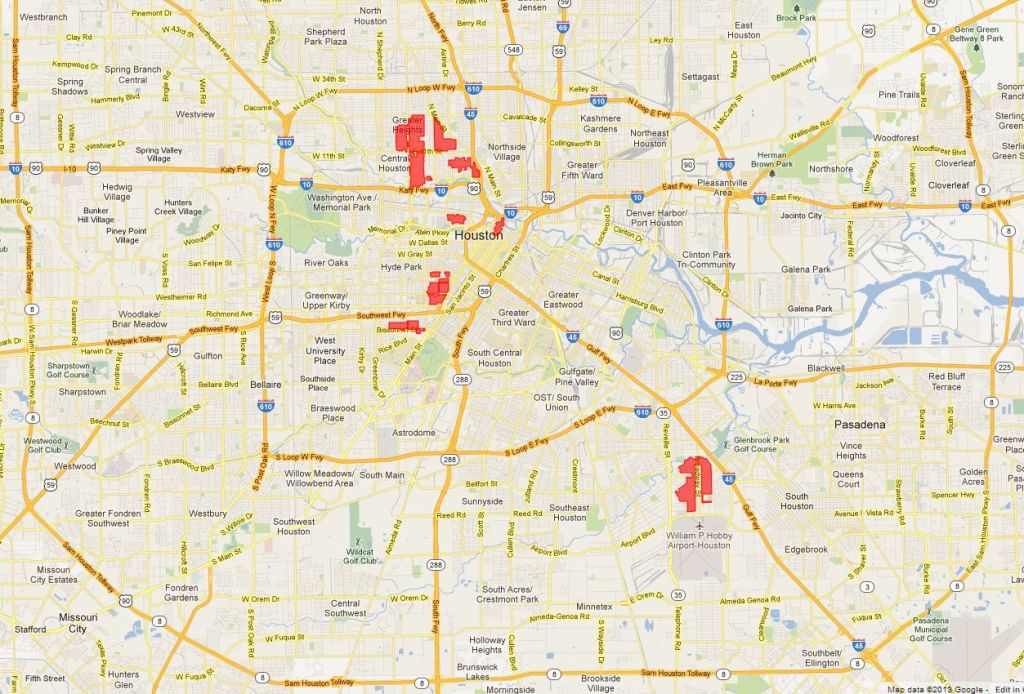

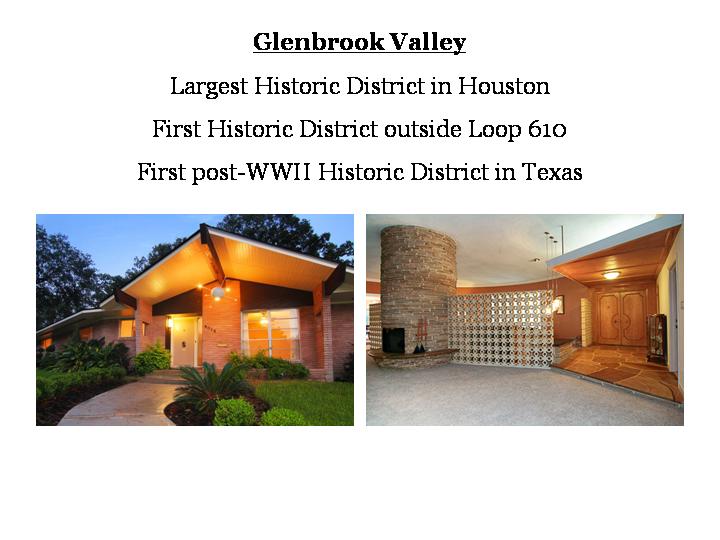

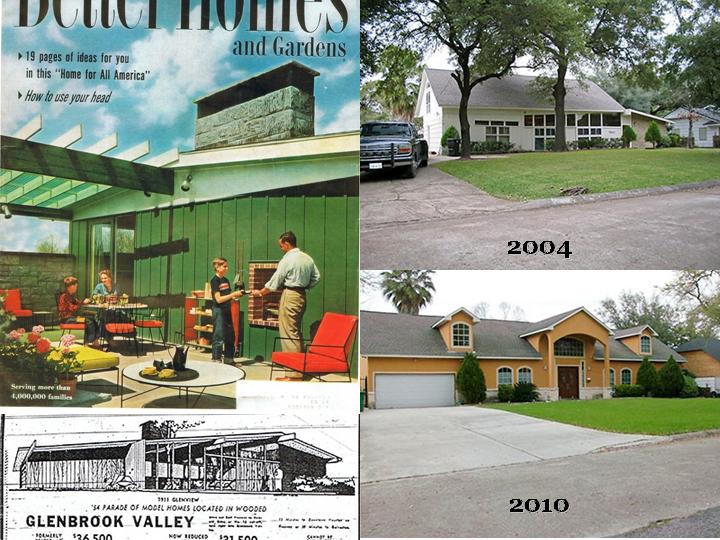

In 2010, the Historic Preservation Ordinance was revised to prevent any demolition of a structure in a Historic District. The above map shows central Houston with the 20 current districts highlighted in red. The cluster near the top is the Heights, followed by Old Sixth Ward and Downtown, then another cluster south in Montrose, and a couple near Rice University. A link to an interactive map can be found here. The neighborhood southeast of downtown, outside the loop, near Hobby Airport is Glenbrook Valley.